A selection of current exhibitions from across the UK – and occasionally further afield – hand-picked and reviewed for Newlyn School of Art subscribers by Martin Holman, art historian and writer on art.

BARBARA HEPWORTH Art & Life

Tate St Ives until 1 May

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-st-ives/barbara-hepworth-art-and-life

The tools a sculptor uses become his friends, and they become intensely personal to one; the most precious extensions of one’s sight and touch.

— Barbara Hepworth, 1961

The senses were very important to Barbara Hepworth. The impressions made on her by looking, touching, hearing and feeling appear fundamental to her conception of form. Hepworth transported the mobile sensations of passing through landscape or experiencing the movement of air, land and sea into the textures, outlines, openings and strings of her sculpture. But she also encapsulated in shape and surface the handling of material. So it presents individual moments when a static object simulates through contour and line, scale and, often, colour, the dynamic instability of the West Cornwall environment. This show is important because it is the biggest gathering of work in many media by this major figure in Western modernism since her death in 1975 – but its size also raises questions about how best to encounter these objects. Although known for sculpture, Hepworth’s paintings and work on paper are also outstanding. Look especially for her hospital drawings of the late 40s and the flowing, gestural drawings inspired by natural forms in the 50s.

VERONICA RYAN

Alison Jacques, London, until 21 January

https://alisonjacques.com/exhibitions/veronica-ryan

Everyday ordinary materials in their own right are very exciting… sometimes things resonate in essential ways for particular thoughts and that determines the choice.

— Veronica Ryan

Ryan was named Turner Prize Winner for 2022 just before Christmas and this exhibition is her first since the award. Ryan has always experimented with materials, using metal, clay, plaster, fabric and dust, and with traditional processes like embroidery and knitting, which also have a personal, family significance for her (as do the threads and pins that can find their way into her work). As an artist in residence in St Ives (working at Hepworth’s palais de danse studio), she became fascinated with how fishermen made and mended their nets, and incorporated nets she made into her sculpture to bundle object-forms. Ryan has long admired Hepworth and her Cornish surroundings although her own background is very different. Ryan was born on the island of Montserrat, a place now almost abandoned by its population following devastating volcanic eruptions since 1995 buried half its territory in ash. Ryan grew up in England but that earlier heritage resonates in her. For instance, submersion is a theme (objects are half buried in larger forms) and she integrates many personal memories into her work through metaphor (her mother, for instance, was a quilt maker). In 2004 Ryan lost an entire body of work in a fire at Momart’s London warehouse. So she decided some years later to recreate that work and place it in conversation with sculptures made in recent years. Certain motifs (like seeds and fruit) recur in recent installations as part of her thinking about migration, womanhood and transposed identities, all of which affect her personally. Ryan’s work is subtle in shape, scale and colour; it can be soft or hard; and it can appear melancholy, ‘quiet’, but curiously comforting, like a familiar possession imbued with meaning.

MAGDALENA ABAKANOWICZ

Tate Modern, London, until 21 May

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/magdalena-abakanowicz

Art does not solve problems but makes us aware of their existence.

— Magdalena Abakanowicz

Abakanowicz, who died in 2017 aged 87, was a pioneer of using fabric fibre as a sculptural material in the 1960s, a decade when artists embraced media that had not traditionally been found in studios. In post-war Poland the strict Soviet aesthetic doctrine of socialist realism was liberalised after Stalin’s death, resulting in a remarkable cultural upsurge in theatre and music as well as art, and the new climate promoted an artistic language that was expressive, intuitive and personal. A few independent, radical galleries also flourished. Abakanowicz emerged as the country’s leading visual artist, combining traditional techniques of weaving with modern abstract concerns for surface, scale, physical sensation and space. There are aspects of performance, too, in this Tate installation of large-scale, coarse and coloured hangings in which the onlooker becomes an actor, improvising meaning from an array of tactile and aromatic ridges, shadows, dyed structures, hollows and hanging threads that suggest a primeval forest or a giant’s wardrobe of garments.

STRANGE CLAY: CERAMICS IN CONTEMPORARY ART

Hayward Gallery, London, until 8 January

https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/art-exhibitions/strange-clay-ceramics-contemporary-art

I’ve thought of myself as an artist for 30 years, but the art world has not.

— Betty Woodman, 2016

Woodman’s comment highlights a continuing divide in the arts between craft and fine art. What’s more the tradition of studio ceramics, exemplified in Britain by Bernard Leach and his St Ives pottery, continues as a constraint for artists using clay sculpturally. That divide is narrowing – in spite of resistance on both sides from makers and critics – and this show takes an international perspective on progress in recent years. Senior exemplars include Woodman and Ron Nagle, a sculptor who works with the vessel form to overcome utilitarian associations and take it into areas hitherto reserved for sculpture. Nagle works on a small scale; by contrast Margate-based Lindsey Mendick is a maximalist, constructing overwhelming, dramatic installations in ceramic, like the brand new ‘Till Death Do Us Part’ (2022). In a rather joyous fashion, the exhibition challenges us to reassess our expectations of the technique.

CEZANNE

Tate Modern, London, until 12 March

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/ey-exhibition-cezanne

The day is coming when a single carrot, freshly observed, will set off a revolution.

— Paul Cezanne

Cymru – National Museum of Wales

Does the world need yet another Cezanne exhibition? It certainly does: Cezanne is one of the most inventive, radical and experimental figures in art’s history. Any opportunity to spend time with this unsurpassed master has to be taken: his vision is incomparable and he reminds us of the importance of sustained observation. The show at Tate Modern – the biggest in Britain since 1996 (and the last big Cezanne show at the Tate) – relates Cezanne to the other Impressionists, contrasting their light-filled landscape and figure compositions with his dark and thickly painted, anxious, indoor subjects of the 1870s, some inspired by newspaper stories and lurid popular illustrations. They have a troubling psychological quality and, indeed, Cezanne emerges as an artist preoccupied with painting as an intellectual activity as much as a visual one. In pursuit of art’s essence, he painted the same subjects over and over – his family and friends, still lives and, of course, Mont St Victoire. His paintings are full of information and knowledge acquired by looking: they go beyond registering reality to weaving a kind of interconnected continuity of form, line and colour that maybe surpasses reality. That’s art. He showed the way to the greatest artistic developments of the last century – to Cubism and abstraction. Unmissable.

LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE: FLY IN LEAGUE WITH THE NIGHT

Tate Britain, London, until 26 February

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/lynette-yiadom-boakye

I think less about the figures than I do about how they are painted.

— Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Yiadom-Boakye paints people. But they are not portraits but created by her from imagination, memory and magazine pages as if they were painted equivalents of characters in written fiction. Her titles are elusive: one is ‘In Lieu Of Keen Virtue’, which explains nothing about the composition. So the viewer has only the marks on the canvas to go by. The bodies boldly fill the canvas as dark shapes might in an abstract image. With time, the subtleties of colour – the blacks that give way to browns, deep reds and purples – become equally as fascinating as the many handsome black men and women she paints in unexceptional surroundings. Yiadom-Boakye’s compelling work is also transfixing – and, well, ambivalent. About its purpose, about its own significance. Instead of these philosophical relationships, she establishes lively communication of another sort – with her audience.

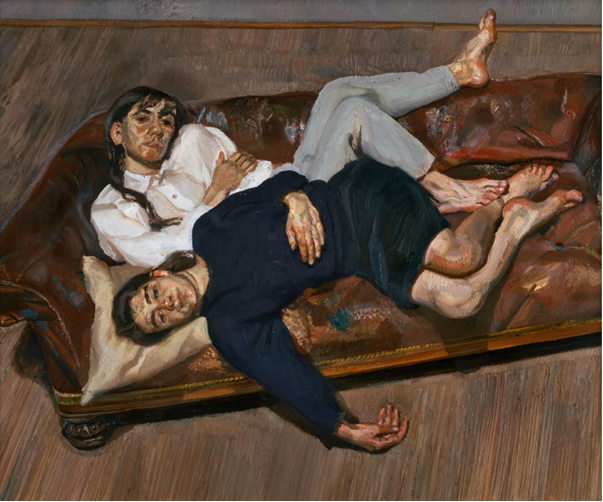

LUCIAN FREUD: NEW PERSPECTIVES

The National Gallery, London, until 22 January

The longer you look at an object, the more abstract it becomes, and, ironically, the more real. — Lucian Freud

Why is Lucian Freud so popular with museum visitors? Since his death in 2011, exhibitions have followed in considerable numbers. That tends to mean one of two things: the artist has ascended to iconic status (like Monet, Picasso – or Cezanne) or will pull in paying audiences. Which is it with Freud? His paintings are seldom comfortable to look at (which is good: the best art raises difficult questions), and his treatment of sitters was confrontational and unapologetic – and cold. Not even portraits of his mother and children solicited a trace of emotional warmth – or, at least, he gave away very little. Instead, Freud pursued a forensic examination of the living so that his oil paint, thickly applied and looking clotted in places, could take on the appearance of human tissue. Bodies could be folded into awkward poses which he insisted the sitters hold for tortuously long periods. With that approach, which he pursued from the late 50s onwards, he explored not only flesh and muscle but also the relationships between him and his subjects. In front of his canvases, we become acutely aware of the one person we cannot see – Freud himself, looking down on the person he is painting and even on us as we look. Is that the ‘new perspective’ this show wants to reveal? Freud may turn out to be Britain’s Old Master of the twentieth-first century.

BARBARA CHASE-RIBOUD INFINITE FOLDS

Serpentine North Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London, until 29 January

https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/barbara-chase-riboud-infinite-folds/

Sculpture as a created object in space should enrich, not reflect, and should be beautiful. Beauty is its function. — Barbara Chase-Riboud

US-born sculptor, novelist, poet and occasional fashion model Chase-Riboud is not well known in this country, although she won a Pullitzer Prize and was one of the first African-American women to exhibit in Whitney Museum of American Art. So this comprehensive survey effectively introduces her to a new audience. She casts sculptures made using a lost-wax process that dates back to the fine Edo bronze work of the kingdom of Benin. She describes her monumental abstract forms as ‘steles’, evoking the ancient Egyptian carved stones at Karnak or Luxor. And they are monuments of a type, often to people who have been missed out for public commemoration for political or racial reasons – or because their achievements were simply not recognised. Malcolm X is among them, a campaigner Chase-Riboud knew, just as she knew major art figures like Max Ernst. Regardless of subject, each sculpture has a generic appearance of pleated sheets of folded bronze or aluminium, combined with long, thick strands of thread. The metal creases in on itself like a crumpled, damaged machine, the fabric twists into neat plaits and ropes. Hence the preference for ‘abstract’ in their description. Chase-Riboud moved to France in the ’50s and lives in Paris and Rome. Her sensibility is European although her motivations remain curiously American. A black woman making art about injustice and freedom. She was awarded the Legion d’Honneur.

FORREST BESS: OUT OF THE BLUE

Camden Art Centre, London, until 15 January

https://camdenartcentre.org/whats-on/forrest-bess

I can close my eyes in a dark room and if there is no outside noise and attraction, plus, if there is no conscious effort on my part – then I can see color, line, patterns, and forms that make up my canvases… I have always copied these arrangements without elaboration. — Forest Bess, 1951

The US has produced some remarkable ‘visionary’ painters. In the nineteenth century there was Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917) and in the twentieth came Forrest Bess (1911-77). Coincidentally both had a connection with the sea: Bess worked as a bait fisherman on a remote island along the Gulf of Texas, spending his nights and off-season days painting. In fact, he would mix sand into his oil paint, thickening the medium into an impasto. He also framed the small paintings with driftwood. The compositions are typically non-figurative and arose from his own intensely private symbolic language which translated into paint the hallucinatory visions he experienced in semi-consciousness before waking. That’s probably why this show is subtitled ‘Out of the Blue’ although it could just as well refer to how little known Bess is in Europe. After his death his work was championed by fellow artists who had also only recently discovered it (although, in life, Bess showed with the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery in New York.) Bess also wrote down these dreams and theorised about them, relating their content to the mythology and psychology he had studied at college. He never studied art, learning techniques instead from a neighbour. He considered his writings as important as his painting and wanted the two exhibited together – which Parsons refused to do. Bess was badly beaten by fellow servicemen in WW2 who suspected he was gay and his symbolism sometimes reflects his research into queer and non-normative identities.

CARRAGH THURING: VOLCANOES

Hastings Contemporary, Hastings, until 12 March

www.hastingscontemporary.org/exhibition/caragh-thuring/

I’ve always been fascinated by their subterranean mystery, and the fact that they destroy themselves as well as build themselves from underneath. — Caragh Thuring

Thuring makes images about the point where manmade and natural meet. For instance, she often paints scenes in which construction is going on. She grew up in Scotland and became familiar with dockyards and off-shore rigs, so that meeting points of that type occur in her work, as do bricks, the essential building material manufactured from organic material. Indeed, figures appear in some of her paintings as silhouettes constructed from lines of brick. As a result, the viewer is on the lookout for visual metaphors. So what to make of the submarines and volcanoes that turn up frequently in this show (hence its title)? Well, here is a possibility: both are ‘built’ but can deliver destruction. As fascinating entities, they harbour unseen destructive powers out of general sight. This line of thought brings the idea to the mind of strength under surfaces: just as bricks that hold up houses are cloaked in plaster rend, so submarines lurk beneath the surface of the water and volcanoes brew lava flows out of sight, channelling their mighty force into the open in bursts of what, poetically, seem like unrestrained fury. Nuclear subs, such as those docked at Holy Loch, near where Thuring grew up, can unleash a greater power from the depths. Thuring’s fascination with construction and breaking down now extends to the cloth she paints on, woven to her specification to include traces of her past work in the threads so that imagery literally becomes the groundwork for her painting.

BHARTI KHER: THE BODY IS A PLACE

Arnolfini, Narrow Quay, Bristol, until 23 January

arnolfini.org.uk/whatson/bharti-kher/

I have lived in India for twenty-five years but my eye will always be different, but then so is everybody else’s eye. — Bharti Kher

© Bharti Kher Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Kher is a British-born artist now living in New Delhi. She is best known for her sculptural installations that imply new relationships that take in formal concerns but also tradition, science, ritual. They are made up of everyday materials that have a past function of their own, appear to defy gravity as they pervade and dissect open spaces. The precarious balancing act of the component pieces inevitably generates a perceptible tension – will the assemblage collapse if I cough? – which makes the viewer pause, look and think. So meditation is a quality here, directed beyond the immediate fascination with objects and their properties towards, perhaps, interpreting the work in terms of science (experiments?) or myth or storytelling. Was the artist’s intention to show, well, the artifice of act or to transform material into pathways towards more poetic or practical interpretations? Kher does not use base materials only but combines them with chunks of precious minerals or bits of statuary – so the visitor wonders what relationships are being probed in these conscious choices. That is also the effect of the pages of story books Kher presents in Arnolfini’s lower gallery, displayed in a network of freestanding steel frames. As with the objects, Kher finds these pages and reshapes them using new words or annotations that change meanings, often with post-colonial or anti-patriarchal recriminations that shift the reader’s perspectives from the intentions of the original writer and illustrator. Large, wall-mounted ‘paintings’ appear abstract but on closer observation incorporate symbolic objects like the bindi, the Hindu drop, or dot worn to denote a ‘third eye’ or the point from which all creation begins. The simple felt dot then spirals out into elaborate designs like a great inclusive formal language connecting Western and Indian art and culture.

And if you find yourself in Paris…

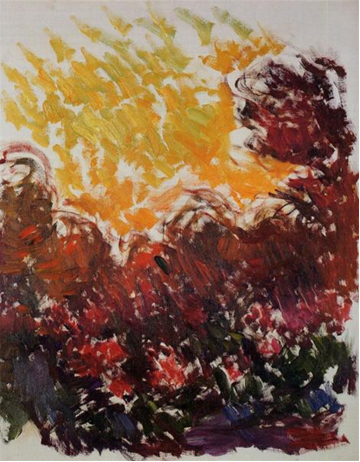

MONET — MITCHELL

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, until 27 February

https://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/en/events/claude-monet-joan-mitchell

Wild with the need to put down what I experience, to render what I feel, I totally forget the most basic rules of painting — if they even exist. — Claude Monet

Sometimes I don’t know exactly what I want [with a painting]. I check it out, recheck it for days or weeks. Sometimes there is more to do on it. Sometimes I am afraid of ruining what I have. Sometimes I am lazy, I don’t finish it or I don’t push it far enough. Sometimes I think it’s a painting. — Joan Mitchell

Monet’s last landscapes, painted in the 1920s when cataracts clouded detail out of his vision and left only effects of light on colour, were dismissed by collectors and dealers at the time and only began to receive critical attention once abstraction was well underway. Their first impact was probably on American artists after WW2. No more dazzling conversation followed than the one celebrated in Paris at the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s stellar exhibition Monet — Mitchell. Joan Mitchell was born in Chicago in 1925, the year before Monet’s death. In 1968 she relocated to a house with lush grounds and a Seine view in Vétheuil, where Monet once lived. Stroke by stroke, we see how he almost anticipates her vivid, colour-rich and paint-ridden gestural approach. Her style evolved in the atmosphere of abstract-expressionism (Pollock, Kline, Still, Rothko) but she rivals Monet in luminosity and improvisational technique, evoking water and foliage in rhythmic though free-flowing choreographies. A truly beautiful and joyous show – with a retrospective of Mitchell’s career tacked on in the spacious basement of the foundation’s extraordinary Frank Gehry-designed home in the Bois de Boulogne. ‘Painting is the opposite of death,’ Mitchell said. ‘It permits one to survive; it also permits one to live.’

Will Cruickshank: Three Moons

Exeter phoenix 11 FEBRUARY - 16 APRIL

https://exeterphoenix.org.uk/events/will-cruickshank/

Will Cruickshank, Spectrum.jpg)

(From left) Will Cruickshank, Spectrum Loop Twist No.2, Yarn, wood and nails, 2023; Code Stick No.3, Yarn, thread and wood, 2022; and Wound Frame No.5, Yarn, wood and nails, 2023. All images © the artist. Courtesy Exeter Phoenix.

Will Cruickshank is based in Devon and works with wood and thread (cotton, wool, synthetic) on constructions that imply something is in the process of being mechanically made. This ambiguous relationship with manufacture is an emergent theme in this sculptor’s work. In previous shows, visitors became a participatory element, operating certain devices. In this show, however, limits and constraints exist; ambiguity lies in these creative works.

Cruickshank works with whatever materials he can find. Thread is sourced at neighbouring factories. While colour is prominent, it is not designed into his work since his “palette” (if that phrase can be applied) is determined by whatever surplus thread is available. The critical ingredients, are the abstract properties like colour, form and line. Colour field painting appears to be alluded to (such as in American painting from the late 50s onwards) and yet the primary impulse appears to be “discovery” or realisation through process and improvisation. Equally compelling are the physical attributes of materiality, texture, tension, motion, wrapping and cutting. Narrative only enters the equation as the viewer attempts to explain the presence of the work.

Ray Hopley: Do Not Disturb My Circles

HWEG, 34 CAUSEWAYHEAD, PENZANCE TR18 2SP FROM 17 FEBRUARY

CALL 01736 688409 FOR DETAILS

Installation of Ray Jopley’s paintings at Hweg. Courtesy the artistand Joe Lyward.

Hopley’s Do Not Disturb My Circles features, unsurprisingly, his canvases made up over recent years featuring concentric circles. Whereas many artists using this abstract form seek to hide their brushstrokes to erase texture in pursuit of a numinous effect, the gesture in the paint here is quite visible. The effect is inevitably slightly hypnotic – in a relaxing way so that the surfaces seem to emit physical sensations in much the same way as we experience changes in light, in the time of day and of weather. By separating these everyday perceptions from the natural world and interpreting them using fundamental, abstract properties in his art, Hopley makes us more aware of the enduring elements of the real world, the sophistication of vision and the interrelationship between colour and feeling.

‘The colour applied empirically,’ Hopley comments, ‘also carries meaning, is elemental and references nature in terms of weather, plants and environment; and also [evokes] feeling, a human response.’

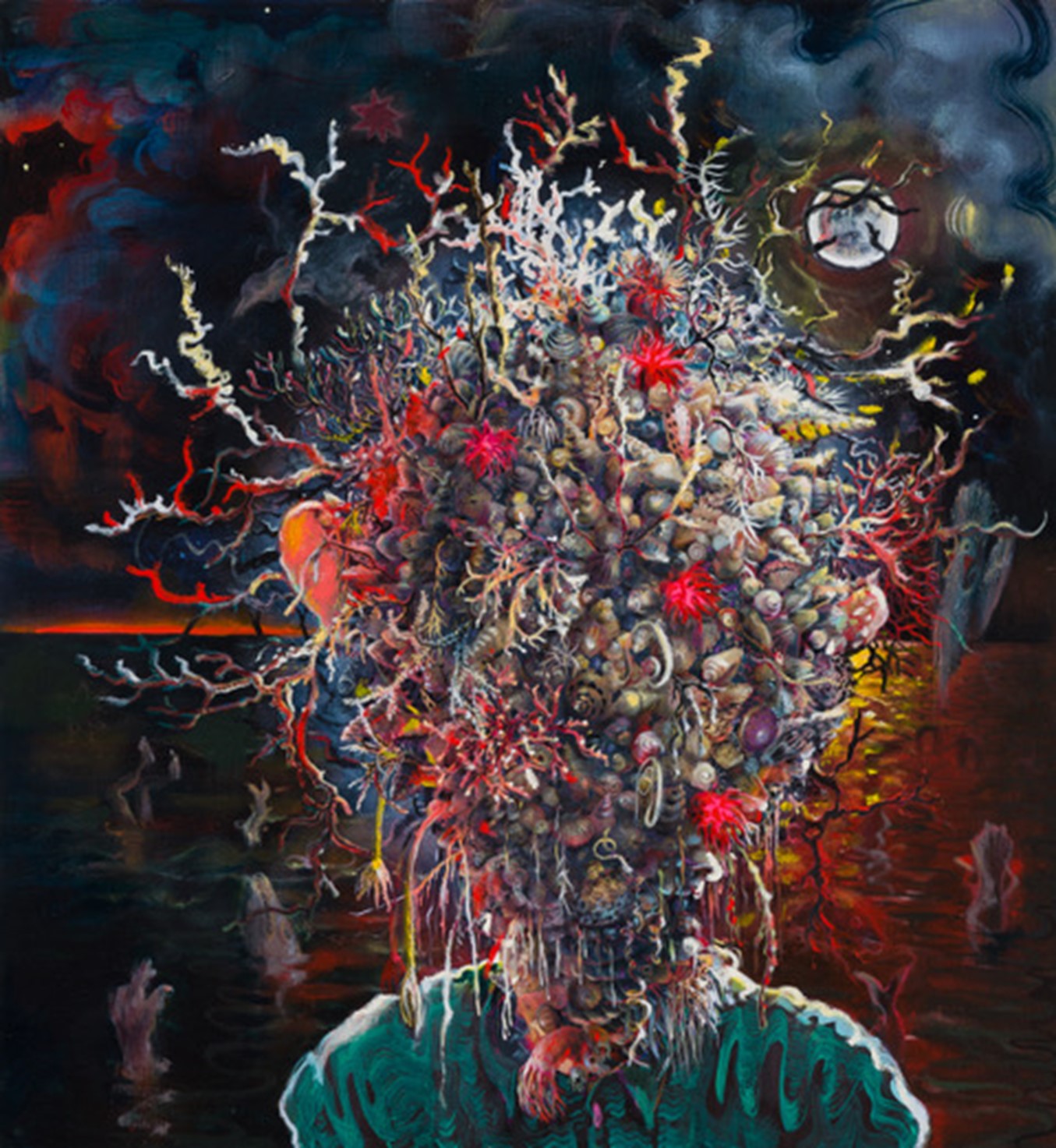

Nicola Bealing Chapter 2: The Borough

MATTS GALLERY NINE ELMS, LONDON 15 MARCH – 16 APRIL

https://www.mattsgallery.org/exhibitions/chapter-2:-the-borough

Nicola Bealing, Drowned Boy, 2020, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist

The second of Helston-based Nicola Bealing’s two consecutive shows at Matts Gallery – one of the best-established London venues for new and experimental art. Both shows feature her distinctive large-scale, narrative paintings, both with sea themes. The first show, however, also featured an installation of ceiling-hung objects like sea creatures, all derived from discarded boat fenders and net floats collected by the artist and her family from beaches on the Lizard. The sea theme comes from Bealing’s fascination since childhood in Malaysia with the underwater world of fluid shapes and bright colours, and from her recent reading of the melodramatic Peter Grimes story of a cruel seaman, written by poet George Crabbe for his collection of narrative poems called ‘The Borough’ (published in 1810). The shows confirm Bealing as a remarkable force in contemporary British figurative painting.

Read my recent feature article about the artist here https://www.drift-cornwall.co.uk/post/a-curious-environment

Denzil Forrester: With Q

STEPHEN FRIEDMAN GALLERY, LONDON 10 MARCH - 8 APRIL

https://www.stephenfriedman.com/exhibitions/173-denzil-forrester-with-q/

Denzil Forrester, Featuring Kaba, 2022, oil on canvas, 153 x 183cm (60 1/4 x 72in). © Denzil Forrester. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery.

Forrester’s big, ambitious and memorable paintings express Black British identity as it emerged around music in the 1970s and ’80s in London and other cities. A constant theme is the dancefloor as point of convergence, either indoors under the distortions of artificial light, or suffused by daylight on the street.

Forrester captures the beat of reggae and its dub variants in his drawing and brushwork, but also the cultural sophistication of a cohesive community. Forrester’s subject matter has remained consistent for 40 years which means it has documented, commemorated and developed with the culture he is expressing. At the same time. Forrester’s work is distinguished by its commitment to painting, its structures, materials and emotional possibilities. Forrester projects a spectrum of sensations from his canvases – anger and fear as well as joy – that seem true to the Black British experience.

Richard Smith: Paintings from the Kite series

VARDAXOGLOU, LONDON 22 MARCH – 22 APRIL

https://www.vardaxoglou.com/exhibition-richard-smith-2023

‘The making of paintings has always been a subject in my work and with the shaping of the canvas this subject became more obvious and in some ways primary… The shape is an aspect of colour, the distortion of the canvas membrane alters the way the colour can be seen – also, the contour makes a varied absorbency, and therefore the canvas holds the colour in a specific way…’

— Richard Smith

Richard Smith gallery instalation shot of Intersections exhibition at Flowers Gallery, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London

Richard Smith (1931-2016) was one the most influential artists active in Britain during the 1960s. A highly original thinker and practitioner, he brought a Pop sensibility to abstraction to establish a novel and distinctive style of painting. First-hand experience of the New York art scene at the end of the 1950s as well as the clamorous street environment of large-scale advertising and vibrant, synthetic open-air colour led him to seek common ground in his work between the modern spectator and high art. Inspired by the billboards in Times Square, he gave paintings titles like ‘Chase Manhattan’, ‘Revlon’ and ‘McCalls’. Complex underlying structures caused the canvases to bulge or reach out along the wall or into the room and, in work from 1972, unstretched, painted canvases were suspended from rods and interrupted by cords and threads hanging off and passing through them. These were his Kite paintings where gravity became a key component. These objects have remarkable beauty and make a gallery look like a colour-filled sail shop. He returned to more conventional flat surfaces in the 1990s, creating space by interleaving painted forms. His astute use of colour never deserted him.

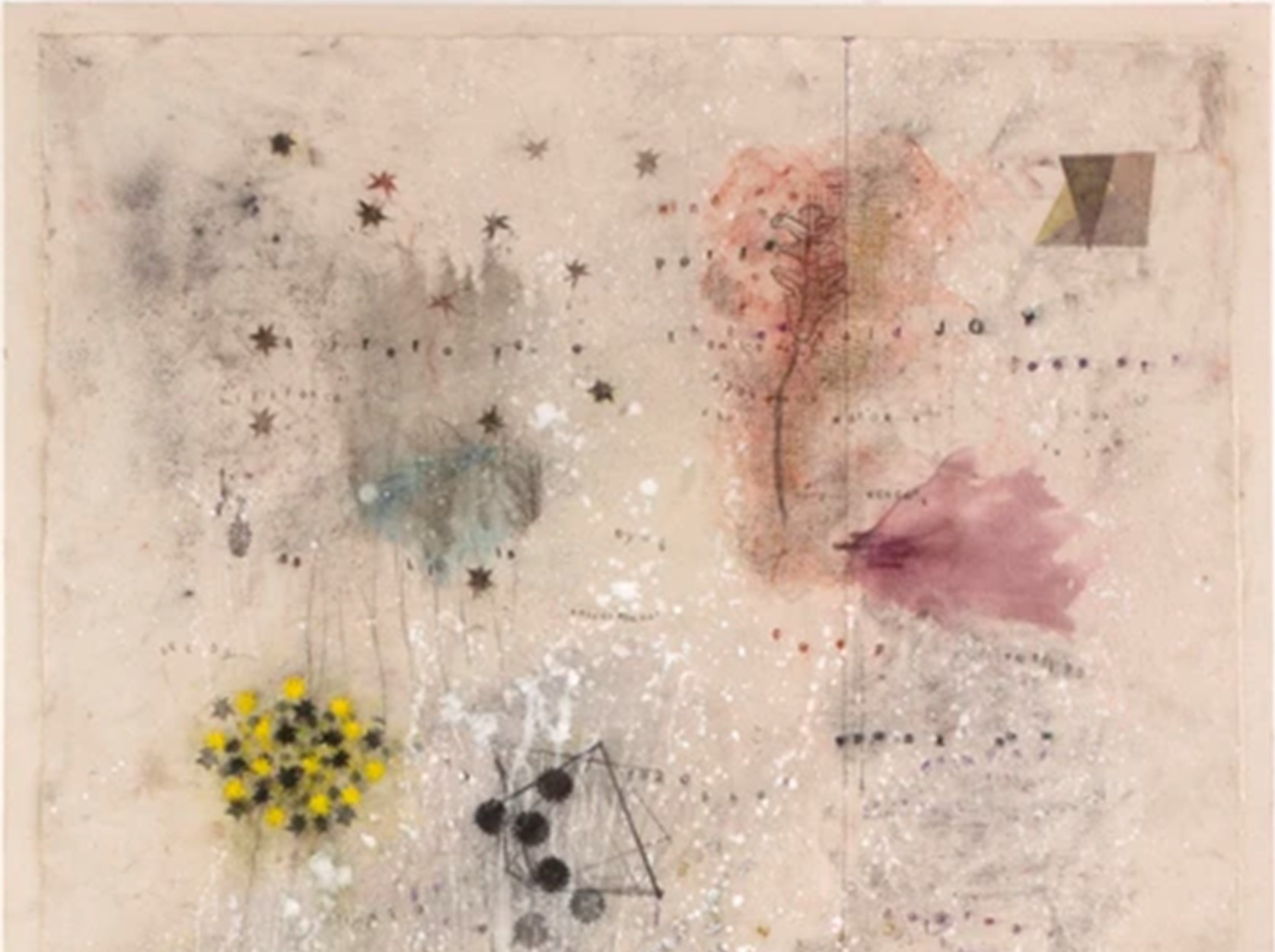

Tricia Gilman: Moment Fields 2019-2023

BENJAMIN RHODES ARTS, 62 OLD NICHOL STREET, LONDON E2 7HP 9 FEBRUARY - 1 APRIL

Tricia Gillman, Threshold II (detail), 2021, charcoal, pastel & acrylic. © The artist. Courtesy Benjamin Rhodes Arts

Mel Gooding, the writer and critic – one of the most perceptive and informed of his generation – who died last year, wrote in 2011 that in Tricia Gillman's work ‘Painting enacts the vertiginous reality of consciousness.’ This observation has been borne out with increasing relevance in her recent work, none more so than in the latest canvases. They contain a surprise: since the 1980s, Gillman (b. 1951) has been associated with colour; yet this new show is notably muted in tone and earthy in character, the result of choosing graphite, charcoal, pastel as her materials.

Gillman has always had an interest in structure and architectural detail, and this element is given fresh prominence. Layering and collage, texture, words and hidden images feature alongside passages of burial, erasure and retrieval. Time, space, interrupted narrative and gesture funnel into the experience of each panel, providing evidence of new expressions being constructed, examined and sometimes then taken apart. Here we experience a personal journey through painting.

Sensing Abstraction

CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY, LONDON 10 MARCH - 22 APRIL

https://cristearoberts.com/exhibitions/

Gillian Ayres, Byblos, 2017, Woodcut, (image size) 115 x 94 cm, edition of 20. Courtesy

An eruption of colour in this selection of abstract drawings and prints by five female abstract artists, each of whose practice revolves around varying approaches to abstraction.

Christiane Baumgartner’s drawings and prints, the making of which the artist likens to the process of handwriting, are shown together with a selection of final prints made by the late Gillian Ayres. Geometric abstraction is further explored through the graphic works of Anni Albers, Rana Begum and Bridget Riley, one of Britain’s greatest living artists. This display coincides with the major exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, ‘Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-70’.

Adelaide Cionbi Ab ovo/On Patterns

MIMOSA HOUSE, LONDON 9 MARCH – 25 APRIL

https://www.mimosahouse.co.uk/adelaide-cioni

Italian artist Adelaide Cioni investigates colour in a way similar to perceiving sound, that is, through its effect on space and the individual within it, experienced as visual rather than aural ‘vibration’. Colour, therefore, ‘resonates’ with the viewer. Her installations capitalise upon this emphasis on sensation. At Mimosa House, with its rooms filled with drawings, installations and repeated abstract patterns, visitors are immersed in colour and a simple yet formal simplicity of structure.

Called Ab Ovo (literally ‘from the egg, from the very beginning’), the installation draws on the recurrence of abstract decorative patterns – stripes, triangles, grids, circles, stylised leaves and stars – both in artefacts and in nature, throughout history and across geographical areas, from early non-western visual imagery to present-day systems.

‘Patterns are the visualisation of a rhythm in space,’ Cioni says. These drawings themselves have a further relationship with sound through her collaboration with a guitarist, whose music she interpreted as forms. Perhaps there is a synaesthesic element: synaesthetes hear colours, feel sounds and taste shapes. And just as colour is sensed here as vibration, so Cioni develops the notion of colour in movement through sound by working with performers dressed in costumes she has designed and which relate to her drawings.

Exhibition round up by Martin Holman exclusively for Newlyn School of Art.

Martin Holman is a British art historian and writer on modern and contemporary visual art. He has a special interest in post-war Italian art and has been closely involved with exhibitions in Britain and Italy. His writing has appeared in the exhibition catalogues of public and private galleries, such as Camden Arts Centre, Haunch of Venison, South Bank Centre and Newlyn Art Gallery, and in newspapers and magazines, among them Art Monthly, Art Review, Burlington Magazine, Daily Telegraph, Frieze, The Guardian, Sculpture, The Times Higher Education Supplement and The Tablet. He lives in Penzance.